Forging new paths in the world of women’s health technologies

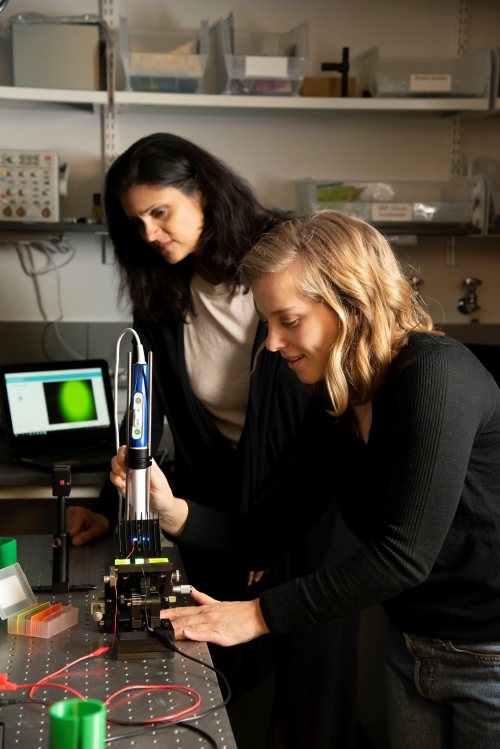

Nirmala Ramanujam, Ph.D., describes herself as a bioengineer, though one who came to it reluctantly. She is the Robert W. Carr, Jr., Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Director of the Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, where she develops imaging and therapeutic tools for cancer, with a special focus on women’s cancers.

While growing up primarily in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, but also with stints in Mysore and Bangalore, India, she was encouraged to play music. Her mother taught her to play the veena, an ancient Indian instrument that is a cousin to the sitar. From age five until her high school years, she applied herself to becoming proficient—even performing for radio broadcasts.

“Music was my outlet to be creative, but I also think that its rules helped me be more disciplined,” she said.

The problem solving and the analytical component in engineering also appealed to Ramanujam, though at first, she thought it lacked the creative aspects of made music enjoyment. Eventually, engineering became a practical way forward, both as a path of study and a way to explore and realize humanitarian goals. She began to see it as a tool that enabled her to find satisfaction, be creative, and apply innovation in designing women’s health technologies.

Ramanujam obtained her higher education—B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees—at the University of Texas at Austin. She progressed through the ranks as an academic researcher in half-decade increments: the first five years as a research scientist and postdoctoral fellow, the next as an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and the following five as an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University. Fast forward another half-decade, to 2011, and the department appointed her as a full professor. She is now an expert in optical imaging, microscopy, and spectroscopy with a multidisciplinary research program to translate these technologies for screening, diagnosing, and treatment for cancers of the breast and cervix. Most recently, her lab has spawned a new area of research in ablative therapy for cancer.

The recurring theme of music as a life-sustaining resource for Ramanujam is never far from her mind and has in some ways blended with her approach to her chosen profession. “It’s not just music for the sake of music; it has to have a broader meaning. That is how I think of engineering. It’s not engineering for the sake of engineering; it’s far more than that.”

A pioneer takes risks

Throughout her academic career, Ramanujam experienced some dissatisfaction with following the prescribed milestones expected of a professor. She reached a turning point as she transitioned from associate to full professorship.

“I realized that I should be thinking about something that I wanted to do that is not just fulfilling the needs to get a promotion or a publication—but being audacious enough to take on unfamiliar challenges that would have a meaningful impact,” she explained. “I went from being risk-averse to having the freedom to be completely pro-risk,” which she concedes was a result of attaining skills, maturity, and confidence through her sustained academic career.

Ramanujam began to focus on the problems she wanted to solve as an engineer and incorporated elements outside of the discipline that made engineering appealing for her.

“I leaned towards that contextual piece that really helped me define what I was interested in, which was women’s health,” she said. “I thought of this as no different than composing a piece of music. Engineering to me is like playing the scales—it is what you do need to know to make the music. Solving a problem creatively is like imagining and then playing the music. Just like music, there is no one path and just as music is a personal expression, so is my view of creating engineering solutions; I want the creation to be meaningful.”

Ramanujam’s seemingly boundless inventiveness is evidenced by the array of multidisciplinary initiatives she has built alongside her teaching and research in biomedical engineering. In 2013, she founded the Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies at Duke University, which aims to make cancer diagnosis, prevention, and treatment more accessible and more effective for women worldwide. The Center partners with more than 50 other organizations, including international academic institutions and hospitals, non-governmental organizations, ministries of health, and commercial partners, to ensure that women-centered health technologies are adopted by cancer control programs in geographically and economically diverse healthcare settings. She started two companies to commercialize the technologies developed at her center.

In addition to her cervical cancer prevention initiative, she has also created a global women’s education program that intersects design-thinking, STEM concepts, and the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals to promote social justice awareness (IGNITE). She also has launched an arts and storytelling initiative, The Invisible Organ, to raise awareness of sexual and reproductive health inequities.

The cavalcade of activities in which she has been engaged has a common wellspring. “They are all connected and come from a place of wanting to create and make something that I believe doesn’t exist in this form and can touch many lives just like a piece of music, which has universal appeal.”

Training the next generation of biomedical engineers

Students in Ramanujam’s courses do not solve math problems with fixed solutions. Rather than getting the right answers, she wants them to understand why they arrived at the specific answers—and can justify how and why technology has an impact and know who benefits from it. For that reason, she does not give exams.

“We debate, discuss ethics, and talk about whether we are giving the best solutions or are compromising care for people who are disadvantaged,” Ramanujam said. “I expect my students to have the maturity to be able to synthesize what they’ve learned to create something new,” Ramanujam said.

An example of a complex problem is the disparity in health services across the globe. “If you’re in a place where there are not many resources, and therefore health outcomes are not good, that’s one kind of problem,” she said. “But if you are in a setting where you spend all the money in the world, but health care is not better, you have a different kind of problem. You can build technologies that serve both worlds.”

“If you make it contextual and emotional and creative, I think they retain a lot more.” Female enrollment in her classes has risen from 30% to 90%. “That’s a good sign; they love the topic.”

Asked whether she fits the role of a trailblazer for women, Ramanujam is quick to find another way to frame the notion. “I wouldn’t say that I’m one of them, I would say that I have benefited from them. You can see what others have done and set the stage for you. Just like 100 years ago when women needed the vote. Someone had to pave the way.”

Nevertheless, Ramanujam has met and faced down challenges to her aspirations in science. “I don’t avoid them, because whether you’re a woman or not, you face challenges, though maybe of different kinds,” she said. “I’ve gone through a lot of things that I didn’t enjoy, but those were what gave me the impetus to do what I wanted to do. That’s how you move forward.”

Through the years, Ramanujam has been successful in obtaining diverse sources of support, and her research projects have been continuously funded by the National Institutes of Health, including grants from NIBIB, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

“The best bioengineering innovation is not necessarily the most expensive nor should it be reserved exclusively for the few,” said Randy King, co-director of the program in Optical Imaging and Spectroscopy at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). “The development of technology by Dr. Ramanujam, with the support of NIBIB, allows access for people from low resource communities to imaging technology they may not otherwise have.”

Ramanujam is a fellow of the Optical Society of America (2009), the American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering (2013), the International Society for Optics and Photonics (2013), and has been elected to the National Academy of Inventors (2017). She has earned numerous awards, most recently receiving the 2020 Biophotonics Technology Innovator Award from the International Society for Optics and Photonics, the Michael Feld Award from the Optical Society of America, and the Abie impact award from the AnitaB Organization.