Because of its high accuracy, laboratory-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is the gold standard for infectious disease diagnostics. Yet PCR requires highly trained staff and costly equipment, hindering its availability, especially in low-resource settings. New research suggests a different kind of test could be more streamlined without sacrificing performance.

A platform technology developed by researchers at the University of Connecticut uses similar techniques as PCR, but within a handheld device rather than several benchtop machines. In a study published in Advanced Science, the authors found that the tool could detect two viruses, HIV and SARS-CoV-2, at a similar level of performance as PCR. With advantages of cost, speed, and portability over traditional methods, the new technology could make powerful diagnostics for infectious disease more widespread.

“As we learned during the pandemic, reliable and convenient diagnostics are instrumental in fighting the spread of infectious diseases,” said Tiffani Lash, Ph.D., program director in the Division of Health Informatics Technologies at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). “Innovations like this that bring additional highly sensitive and accurate testing to the point of care could become invaluable tools for the rapid diagnosis of a range of infectious diseases.”

Some of the most common tests for infectious disease detect either viral material called antigens or proteins produced by the immune system in response to infection known as antibodies. Despite the reliability, speed, and widespread availability of these tests, which include the now prevalent COVID-19 rapid antigen tests, PCR still holds an advantage in terms of accuracy, which can be nearly 100%.

PCR’s strength as a diagnostic tool comes from its ability to detect the genetic material, such as RNA, of pathogens directly. This approach provides greater specificity, meaning it is less likely to mistake non-pathogenic particles for the target and produce a false positive result. PCR also amplifies the target it is looking for to make it sensitive to smaller amounts of pathogenic material, meaning even a low-level of infection can be detected.

As it stands, patients and health care providers often need to choose between technology that is easy to access and use and technology with high performance. Changchun Liu, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Connecticut, and colleagues aimed to break down this dichotomy.

Matching the gold standard

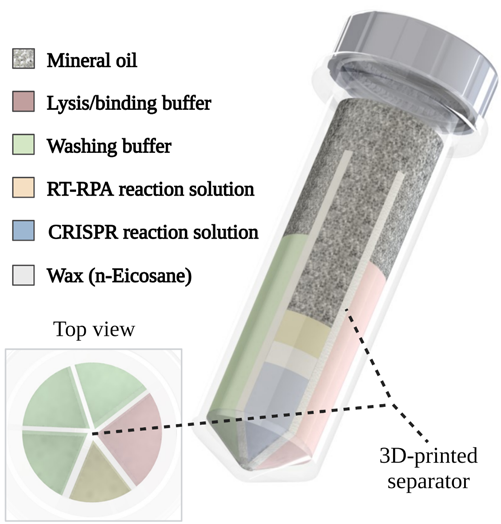

The team’s proposed solution is the lab-in-a-magnetofluidic tube (LIAMT) — a device composed of a 1.5-milliliter tube containing a 3D-printed insert and a wireless handheld processor. Whereas PCR involves the use of several benchtop machines, LIAMT is a portable one-stop-shop that performs similar processes.

Key differences allow for drastically slimmed down hardware and simplified user training, Liu explained. One major difference is in how LIAMT isolates genetic material from biological samples.

Whereas traditional techniques rely on fast-spinning machines called centrifuges to separate lighter nucleic acids from the rest of the sample, LIAMT relies on magnetism. Tiny magnetic beads within the tube stick to viral RNA in the sample through the attraction of electric charges on the molecules. Then, after a user places the tube within the handheld processor, a magnet inside the device pulls the RNA-bound beads through several washing steps in the tube, filtering out unwanted material.

Once genetic material is isolated, PCR copies specific stretches from a virus’s genetic code millions to billions of times over so it can be detected more easily. This step entails many cycles of heating and cooling to facilitate the separation of paired nucleic acid strands and their subsequent duplication, which requires specialized thermal cycling equipment.

LIAMT instead incorporates a recent PCR-alternative that employs special proteins that are able to split up and amplify nucleic acid strands at a low and constant temperature.

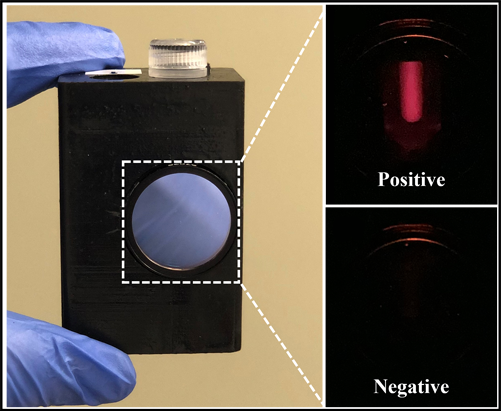

After amplification, the wireless LIAMT device heats the sample by a few degrees, melting a wax barrier in the tube and releasing a solution of CRISPR enzymes that results in the emission of a fluorescent signal after they bind to their target.

If enough viral RNA was present in the initial sample, then that signal can be viewed through a small window in the LIAMT device, indicating a positive test result.

Free of the burden of a centrifuge and thermal cycler, the portable LIAMT could be used in a clinic or in a home. The diagnostic tool can also produce results in about an hour, which is much faster than PCR usually takes, as test sites often do not have the necessary equipment (meaning samples need to be shipped off site for analysis).

Developing an accessible device was just half the battle, however. It also needed to hold its own against PCR.

To test their diagnostic tool, the researchers obtained 32 swab samples from patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 and 41 blood plasma samples from patients tested for HIV. They used both LIAMT and traditional PCR to search for viral RNA within the samples and compared the outcomes.

The study authors found the sensitivity and specificity of LIAMT to be promising for both viruses. And when compared to PCR, LIAMT’s designations of whether samples were positive or negative aligned for 29 of the 32 swab samples and 40 of the 41 plasma samples.

Encouraged by these results, Liu seeks to continue developing the LIAMT platform, finetuning its performance and usability. He is particularly motivated by the possibility of improving care for people with HIV, who often need to undergo routine testing to receive treatment, which involves hospital visits, having blood drawn, and days of waiting for results.

“With our device, we used the volume you could get from a finger prick to produce accurate HIV test results quickly. Patients could take these tests at a local point-of-care center or at home and receive the medication they need more quickly,” Liu said.

This research was supported by grants from NIH, including NIBIB (R01EB023607) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; R33AI154642), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH; R21OH012194).

This science highlight describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process—each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

Study reference: Ziyue Li et al. Palm-Sized Lab-In-A-Magnetofluidic Tube Platform for Rapid and Sensitive Virus Detection. Advanced Science. DOI: 10.1002/advs.202310066

About the graphics: These two images originally appeared in the Advanced Science paper and are available under the Creative Commons license. Images have been adapted for the NIBIB website.