NIH-funded researchers restore facial nerve function in animals with stem cell-based conduits

A gesture as simple as a smile can often convey what words cannot. This is part of why nonverbal communication is so central to human interaction. It is also why facial nerve disorders and injuries can be devastating.

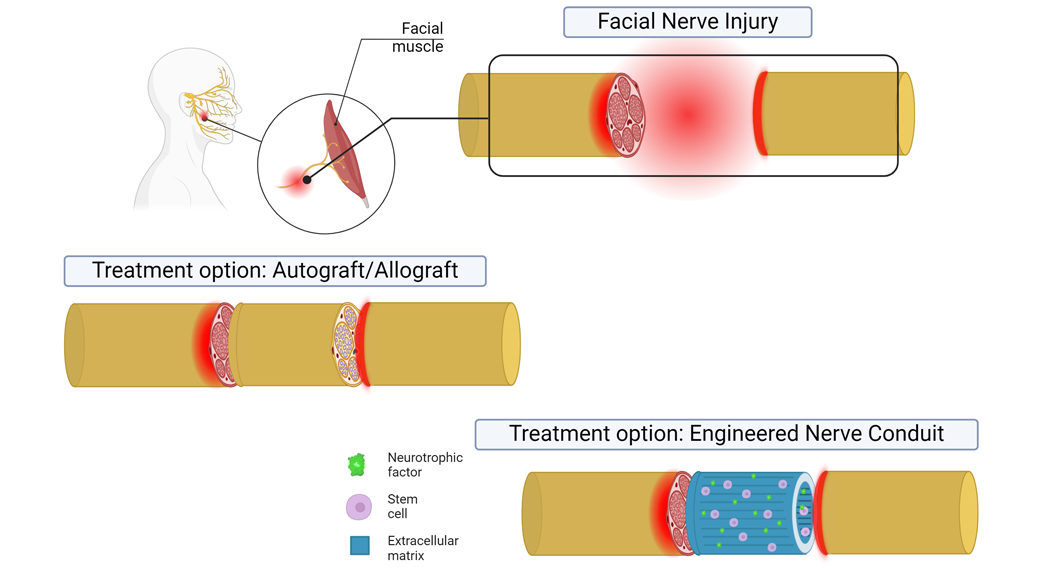

These conditions are typically treated with nerve tissue taken from elsewhere in a patient’s body, known as autografts. This technique for repairing injured nerves presents issues for patients, such as damage to the donor site and the odds of functional recovery being nearly a coin toss. Synthetic alternatives have been explored in the past but have yet to live up to the performance of autografts.

Bioengineers at the University of Pittsburgh may have developed a new solution with the help of some of nature’s best engineers — stem cells. Leveraging these cells’ ability to create a restorative environment, the team produced implantable conduits to act as bridges, providing directional, mechanical, and biochemical guidance for injured nerves to regenerate across large gaps. Experiments in the facial nerves of rats showed that the technology matched autografts. These results were published in the Journal of Neural Engineering.

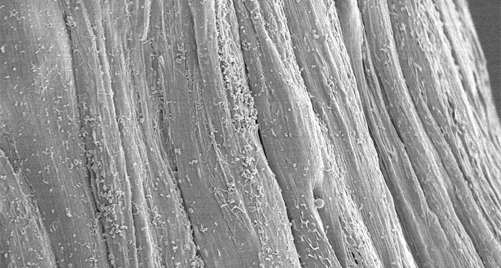

“We leaned into the idea that the cells know what they're doing, and they know how to make tissue,” said oral and craniofacial sciences and bioengineering professor Fatima Syed-Picard, Ph.D., the senior author of the study. “These engineered tissues ended up being more biomimetic than many other synthetically derived scaffolds used in tissue engineering.”

Getting neurons in line

For nerves to be repaired, the long projections that extend from neurons, called axons, need to both regrow and reconnect to the appropriate tissue. With autografts, the former is slow, and the latter is no guarantee, as many patients experience unwanted muscle activity due to regrown nerves connecting to the wrong tissue.

Researchers have wielded specific cell populations to accelerate growth, such as neural support cells and stem cells, which produce biomolecules that aid neural tissue regeneration. To orient growing tissue so that axons reach the proper targets, researchers have designed synthetic tissue scaffolds with features, such as grooves, that act as guiderails to regenerating neurons.

“It’s difficult to embed and distribute cells evenly in synthetic scaffolds without harming them. Another concern is trying to get these scaffolds to match the structural complexity of innate tissue,” said first author Michelle Drewry, Ph.D., who conducted this research while a graduate student* at the University of Pittsburgh.

Many cell types in the body frequently make or remodel the biomolecular scaffolding surrounding them, known as extracellular matrix (ECM). So, instead of making tissue scaffolds from scratch themselves, the researchers thought it might be better to let cells make their own. The authors of the study tested this hypothesis with dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), a hardy and readily available cell population that produce proteins known to encourage nerve growth. After extracting these cells from adult wisdom teeth provided by the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, the researchers put them to work.

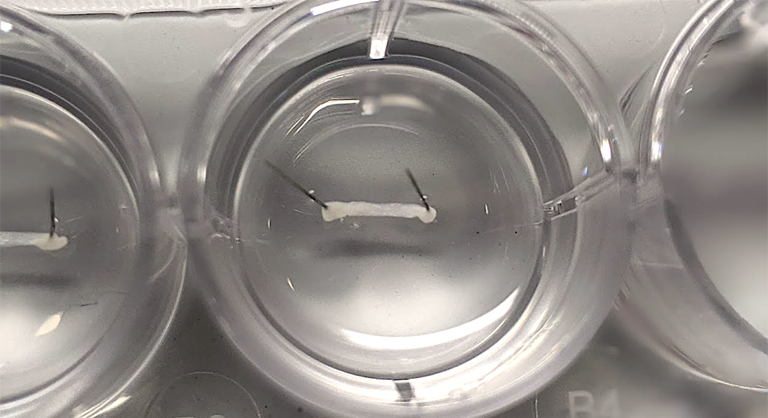

They wanted to give DPSCs the freedom to create ECM but, at the same time, nudge them into making an environment conducive to supporting aligned axons. To accomplish this, the researchers fabricated rubber molds with rows of 10 micrometer-wide grooves and then covered them with DPSCs. After several days, the DPSCs secreted aligned ECM around themselves, forming thin biological sheets. The authors then peeled the sheets from the rubber templates and rolled them up into cylindrical conduits.

The researchers used this approach to make a type of bandage in a previous study, which successfully regenerated the axons of a crushed nerve. With their new work, they sought to clear a higher hurdle of using the conduit to bridge a 5-millimeter gap in the facial nerve of rats — a defect so large that the nerve would not be able to heal on its own.

Specifically, they implanted their aligned conduits into gaps made in the buccal branch of the facial nerve. For comparison, the team also implanted autografts into another group of rats.

“The buccal branch is the part of the facial nerve that helps with smiling. It's a big part of your quality of life because it’s a large piece of how you communicate with other people and how you're seen in the world. Injury to that nerve can have a life-changing effect,” Drewry said.

Crossing the bridge

Twelve weeks after implantation, the authors evaluated how well axons had regenerated, primarily through histology. They found that their cell-made conduits contained regenerated axons across their full length. And, in general, the density and number of axons were similar to what they found in autografts.

Indicators of developing axons were prevalent in the conduits, suggesting that regeneration may have been more robust with additional time, Drewry noted.

But did all this regenerated tissue translate to improved function? To find out, the authors electrically stimulated the nerves on one end and measured the animals’ whisker movement on the other side. The tests showed that the motions of rats implanted with conduits were on par with those treated with autografts.

Syed-Picard’s lab aims to better understand the roles the ECM and cells play in healing and then use that information to improve their technology. For example, in addition to encouraging regrowth directly, the conduits may also be helping by dampening inflammation, Syed-Picard explained.

Drewry’s work on this study was funded by the Cellular Approaches to Tissue Engineering and Regeneration (CATER) Training Program at the University of Pittsburgh, which is supported by NIBIB grant T32EB001026.

“This research exemplifies how our training programs lay a strong foundation for doctoral students. Trainees from this particular program have gone on to receive 58 subsequent NIH grants including fellowships, career awards, and research grants,” said Zeynep Erim, Ph.D., director of the Division of Interdisciplinary Training at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

The research was also supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR; R56DE030881).

This science highlight describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process—each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

*Drewry is now an associate program officer at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Her comments in this article reflect her personal views and not that of NASEM.

About the graphics: These two images originally appeared in the Journal of Neural Engineering paper and are available under the Creative Commons license. Images have been adapted for the NIBIB website.

Study reference: Michelle Drewry et al. Enhancing facial nerve regeneration with scaffold-free conduits engineered using dental pulp stem cells and their endogenous, aligned extracellular matrix. Journal of Neural Engineering (2024) https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ad749d