In NIBIB study, bone marrow transplantation during adolescence but not adulthood protected animal arteries

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) can potentially cure sickle cell disease, an inherited and painful blood disorder, but because of its potential drawbacks and costs, patients and caregivers often face the difficult decision of whether to undergo the procedure. However, new research suggests that earlier BMT may provide protection from stroke later in life.

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine, researchers at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) and the Georgia Institute of Technology examined arterial damage in mice with sickle cell disease that received BMT either in adolescence or adulthood. The team found that younger recipients were protected into adulthood from widening arteries — a process that increases risk of stroke. In contrast, the arteries of older recipients, which had already expanded by the time of treatment, only continued to worsen afterward.

“We saw that if you wait until after the vasculature is damaged to do this procedure, the tissue doesn’t bounce back,” said NIBIB senior investigator Manu Platt, Ph.D., corresponding author of the study. “Down the line, this could be another key piece of information that is a motivator for earlier interventions.”

In sickle cell disease, hematopoietic stem cells residing in bone marrow contain a genetic mutation that leads them to produce misshapen red blood cells. These crescent-shaped cells become sticky, clumping together and adhering to arterial walls, which alters the way blood flows. They are also more rigid than healthy cells, making them prone to bursting as they travel throughout the body.

These effects can damage or clog critical blood vessels, such as the carotid arteries that supply the brain with oxygen, setting the table for a stroke to occur, which is the case for more than a tenth of patients with sickle cell disease under the age of 20. An even larger fraction of 37% may have a silent, or asymptomatic, stroke before turning 14.

BMT can offer patients a new source of healthy blood, but first the mutated stem cells in their bone marrow must be removed, usually through high-dose chemotherapy, which presents a host of risks, including infection, gastrointestinal issues, and infertility. Normally, patients undergo this treatment only if their symptoms are severe and if an ideal donor — such as a healthy sibling — is available.

While two recently approved gene therapies for the treatment of sickle cell disease could bypass the need for donors, this option is currently unavailable to most people. And patients would still need to undergo chemotherapy first, Platt explained, meaning many candidates may nevertheless be reluctant to be treated.

Despite the curative potential of BMT, damage wrought by sickle cell disease before treatment can still echo throughout a patient’s life. Past research shows that a significant fraction of adult patients still experience a stroke after treatment, but what has been less clear is what role the timing of BMT plays, and whether or not earlier is better.

Platt and his colleagues at the NIBIB’s Section on Mechanics and Tissue Remodeling Integrating Computational & Experimental Systems (MATRICES) and Georgia Tech sought to pull at this thread using a mouse model of sickle cell disease.

After exposing animals to a chemotherapy regimen, the researchers performed BMT when mice were either 2 or 4 months old to model treatments performed in adolescence or adulthood, respectively. The team used magnetic resonance angiography, a kind of magnetic resonance imaging, to measure how much the lumen, or opening, of the animals’ carotid arteries had expanded at one month prior to BMT, and then at one and three months afterward.

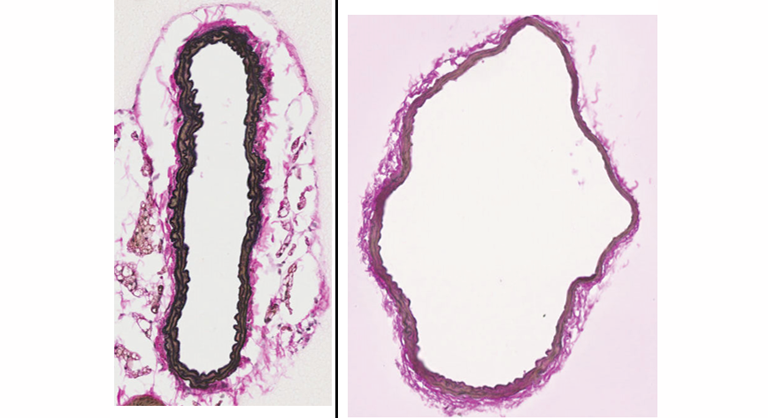

The study authors found that the arteries of younger BMT recipients were similar to vessels from a healthy group across the time points. On the other hand, the arteries of 4-month-old (adult age in mice) recipients continued to widen following BMT, much more closely matching the lumens of diseased mice that received no treatment.

After three months, the researchers placed arterial tissues from a younger BMT group under a microscope for closer examination. This time, rather than looking at the lumen, they evaluated the perimeter and thickness of artery walls, finding more evidence that early transplants protected tissue from pathological changes.

The team also saw indications of early BMT protecting the liver and spleen, and, in future work, plan to continue understanding the effect of BMT timing across the body.

“The arteries go everywhere, right? If there’s arterial damage somewhere due to this hematological disease, then we want to see if earlier transplants can make a difference,” Platt said.

The research was supported by the NIBIB Intramural Research Program and a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; R01HL158159).

This science highlight describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process—each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

Study reference: Liana Hatoum et al. Bone marrow transplant protects mice from sickle cell-mediated large artery remodeling. Science Translational Medicine (2025). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.adp7690