Study in sheep effectively modulated deep brain regions without drilling into the skull

Deep brain stimulation—the application of electricity to specific deep brain regions to modulate their function—has been used clinically for over 25 years. This technique is used to monitor and treat neurological conditions, especially movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy. Yet many of these interfaces are highly invasive, as they require removing part of the skull to implant electrodes in the brain. Finding a way to monitor and stimulate the central nervous system in a less intrusive way has been a holy grail for those in the neuromodulation field.

Now, a collaborative team of NIH-funded researchers at Rice University and The University of Texas are developing a method to access and stimulate deep brain regions without drilling into the skull. They engineered a tiny pulse generator that can be implanted in the spine following a lumbar puncture. This pulse generator is connected to a stimulating catheter, which can be guided through the cerebrospinal fluid to the surface of the brain. After preliminary experiments in human cadavers, the team successfully used the device to record and stimulate brain activity in sheep with the aid of a wireless interface. Their work was recently published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“Using our technique, we demonstrated that it is possible to place an electrode in the brain using a relatively simple lumbar puncture, avoiding the need for a craniotomy,” said study author Jacob Robinson, Ph.D., a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rice University. “By reducing the invasiveness of deep brain stimulation, we hope that our research will help to reduce the barriers of this technology and someday provide improved therapies to patients with neurological disorders.”

Deep brain stimulation devices typically consist of two major components: an electrode, which is in direct contact with the brain, and an implantable pulse generator, which controls the electricity delivered to specific brain regions. Traditional pulse generators for deep brain stimulation are implanted under the skin near the collarbone and require a battery; electrodes are typically inserted through holes in the skull in order to reach the necessary brain regions.

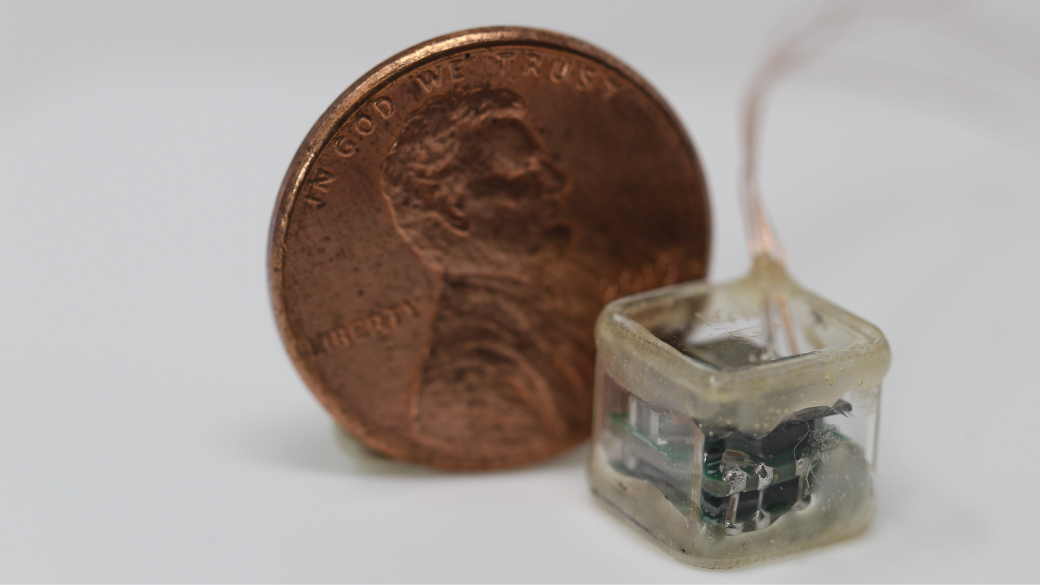

The proof-of-concept neuromodulation device described in this research contains the same basic components, yet they’ve been optimized to reduce the invasiveness of traditional deep brain stimulation interfaces. The implantable pulse generator has been miniaturized, measuring roughly 1cm in each dimension, and it doesn’t require a battery—instead, the device is powered by magnetoelectric films, which can be activated by an external magnetic field. And rather than drilling into the skull to place an electrode, the researchers have developed a method to snake a stimulation catheter through the endocisternal space, or the plumbing that carries the cerebrospinal fluid throughout the central nervous system. This technique allows the team to place electrodes in the brain using a minimally invasive approach, which could potentially improve the safety and recovery time of deep brain implantation. Both the pulse generator and the electrode could enter the body through a small incision in the lumbar spine in the lower back.

“The brain has several ventricles, or fluid-filled cavities, which are located deep within the brain, and these ventricles connect to other brain regions and the spinal cord through a series of passageways,” explained study author Peter Kan, M.D., a neurosurgeon at the University of Texas Medical Branch. “With the assistance of x-ray imaging, we can use these fluid-filled passageways to carefully steer the electrode up the spinal column and into specific deep brain regions, all without having to open up the skull.”

The researchers first assessed their method in human cadavers, finding that they could insert the stimulation catheter into the spine and successfully guide the electrode to specific regions deep in the brain. Next, the researchers wanted to evaluate how well their device could stimulate deep brain regions in a live animal. To do that, they turned to a common model used in human spinal research: sheep.

After implanting the pulse generator in the lower spine and guiding the electrode into the ovine brain, the researchers used an external magnet to wirelessly activate the neural interface. As expected, the researchers could stimulate the motor cortex, as evidenced by muscle contractions in the animals’ hind legs. Further, the researchers demonstrated that they could stimulate deep brain regions and subsequently detect the corresponding activation of the central nervous system through the evoked potentials (or electrical signals) measured in the spinal cord.

“We also demonstrated that we can place two electrodes—one in the animal’s brain, and the other in the spinal cord—and activate them simultaneously,” explained Robinson. “Multi-site access allows for the coordinated activation of multiple regions of the central nervous system, which is an important technique in neuromodulation therapies.”

The researchers evaluated the long-term viability of the device in two of the 12 sheep. After 30 days, they found that the implant could still effectively stimulate the central nervous system. What’s more, the animals didn’t display any neurological deficits.

“This device, while still in an early phase of development, has the potential to bring neuromodulation implants to more patients, making deep brain stimulation devices as ordinary as cardiac pacemakers,” said Moria Bittmann, Ph.D., a program director in the Division of Discovery Science and Technology at NIBIB. “Future work will ensure that the technology is safe before it is evaluated in humans.”

This study was supported by a grant from NIBIB (U18EB029353).

This science highlight describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process—each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

Study reference: Chen, J.C., Dhuliyawalla, A., Garcia, R. et al. Endocisternal interfaces for minimally invasive neural stimulation and recording of the brain and spinal cord. Nat. Biomed. Eng (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01281-9