New research suggests that engineered tissues could one day do some of the work of traditional electrical stimulation devices while offering more customizable and biologically friendly solutions.

A team of NIH-funded researchers produced 3D-printed scaffolds using a special ink containing tiny solar cells. By shining lasers on their light-sensitive material, they were able to influence the contractions of cells seeded within and around their device, going as far as to successfully regulate heart rate in an animal experiment. Their results are described in Science Advances.

“The future of bioelectronics is not just creating a device and putting it on a shelf to be put into the human body later,” said co-corresponding author Cunjiang Yu, Ph.D., a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “We’re starting to print custom technologies with living tissues that could integrate harmoniously with the body. This approach could have tons of therapeutic opportunities.”

Implantable electrical stimulation devices, such as pacemakers and spinal cord stimulators, modulate tissue function to treat a wide variety of injuries and diseases, from heart attacks to chronic pain. Traditionally, these devices deliver electrical current through wires, or leads, wedged into tissue, which creates a risk of injury and infection, especially for long-term applications.

Although recent studies have explored ways to cut the cord for electrical stimulation devices, the authors of this new paper aimed to develop a solution unrestrained by traditional electronics that could take on any form.

“If you’re thinking about an actual wound area, oftentimes, it’s not a flat surface,” said co-corresponding author Y. Shrike Zhang, Ph.D., associate professor and associate bioengineer at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “With our 3D printing method, we have total control of the structure of the engineered tissue. Down the road, it could essentially be used for any electrically active tissue.”

So, how does one create tissue that produces electrical activity on demand?

A method that researchers have used in the past is to genetically modify cells so that they perform a desired activity in response to certain kinds of light. While a useful research tool, a method based on genetic modification would face many barriers to clinical translation. The authors applied this general concept, but removed the genetic component, instead engineering tissue scaffolds to convert light into electricity using photovoltaic, or solar, technology.

The basic building block of solar panels, called solar cells, are thin, square wafers usually made of silicon that are a few centimeters wide. To stimulate heart tissue, the researchers produced solar cells that were close to a single micrometer in thickness and tens to a hundred micrometers wide. The researchers mixed these microscopic solar cells into gelatin methacryloyl, a biologically derived hydrogel commonly used in tissue engineering, to form their unique bioprinting ink.

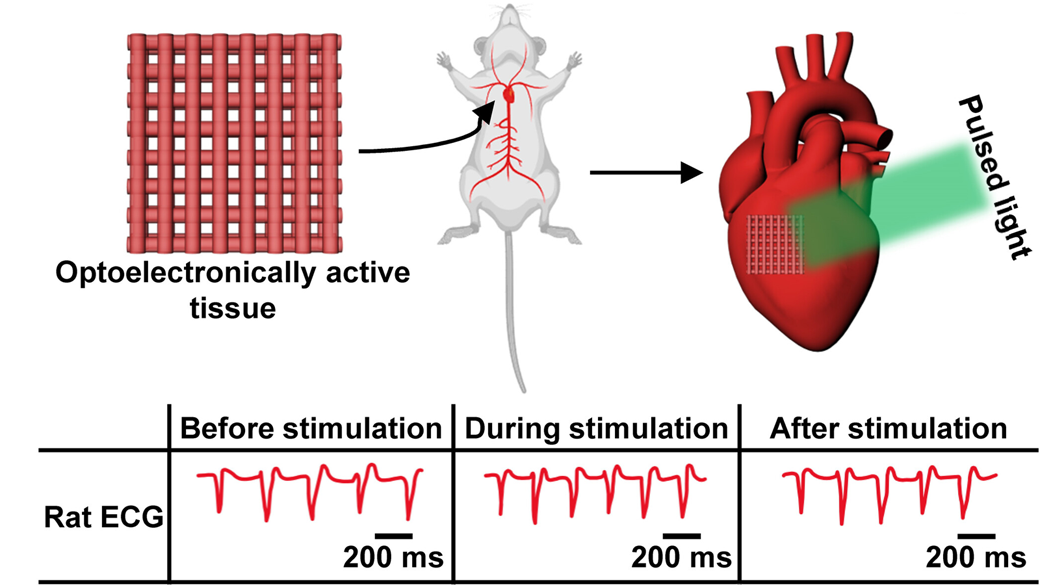

They printed grid-shaped scaffolds and tested them through several benchtop experiments, verifying that the material was not toxic and could stimulate rhythmic contractions in heart muscle cells in response to light.

Next, the team sought to examine the engineered tissue’s performance in the presence of a beating heart. The researchers loaded a sheet of printed scaffold with rat heart cells and then surgically implanted it in a live rat, on the heart’s surface. They specifically placed the tissue above the right atrium of the heart, near the cluster of cells that act as the heart’s natural pacemaker.

The authors shone light from a green LED on the implant with the goal of speeding up the animal’s heart rate. After 12 minutes of stimulation, the beating rate increased from approximately 280 beats per minute to the target rate of 300 beats per minute.

While the authors are counting this test as a win for their new platform technology, they also have many new questions. Given the short duration of the test — and similar results achieved in another experiment where no heart cells were added to the scaffold — the authors propose that the solar cells in the scaffold were the primary means of regulating heart rate.

“The work is an exciting proof of concept. It will be key to see how this technology integrates with native tissue and how it could be implemented for long-term use,” said David Rampulla, Ph.D., director of the Division of Discovery Science and Technology at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). “This novel union of soft biomaterials and electronics could certainly open doors.”

In addition to investigating the bioprinted tissue’s performance over longer spans of time, the authors intend to investigate its ability to treat injuries and diseases, such as correcting arrhythmias or replacing tissue damaged after a heart attack.

The researchers plan to explore methods of implementing a light source in the body down the road. The team could potentially leverage wireless charging technology and recent biocompatible optical fiber technology, explained Yu, which could allow them to maintain the minimally invasive nature of their approach.

This study was supported in part by grants from NIBIB (R21EB026175, R21EB030257, R01EB028143, and R56EB034702), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R21HL168656 and R01HL166522), and the National Cancer Institute (R00CA201603 and R01CA282451).

This science highlight describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process—each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

Study reference: Faheem Ershad et al. Bioprinted optoelectronically active cardiac tissues. Science Advances (2025). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt7210